Rebating the Stock Transfer Tax is Called the ‘Dumbest’ Thing NY Has Ever Done—So, Why Are We Still Doing it?

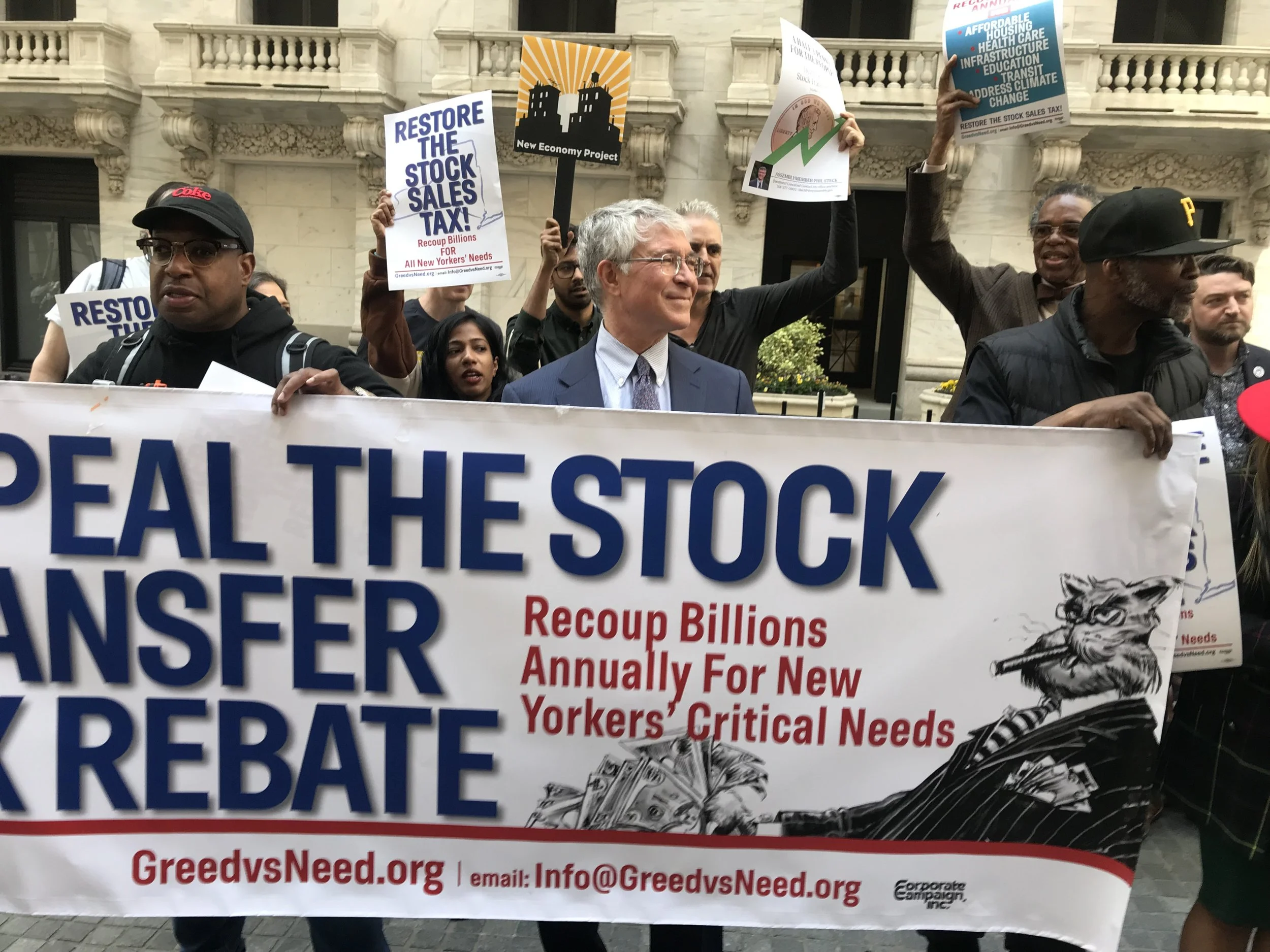

Assembly Member Phil Steck (middle) and State Senator James Sanders Jr. have reintroduced a bill to repeal New York State’s stock transfer tax rebate. Photos/Steve Wishnia

By Steve Wishnia

New York State has been rebating billions of dollars in stock-sales taxes to Wall Street for more than 40 years—and legislators and activists are making another try to change that.

State Senator James Sanders Jr. (D-Queens) and Assemblymember Phil Steck (D-Albany) have reintroduced a bill to restore the state’s stock transfer tax, which was enacted in 1905 and phased out in the late 1970s. Since 1981, the state has reimbursed 100% of payments collected, which range from 1.25 cents on shares sold for under $5 to 5 cents on shares sold for $20 or more.

Steck estimates the state would gain $14 to $16 billion a year in revenue from reviving the tax.

“For just half a penny in stock transfer, we could have billions for trains, for housing,” Sanders, chair of the Senate Banking Committee, told a rally of about 50 people outside the New York Stock Exchange Apr. 23. “You say, ‘it’s ridiculous not to do this.’ I agree with you.”

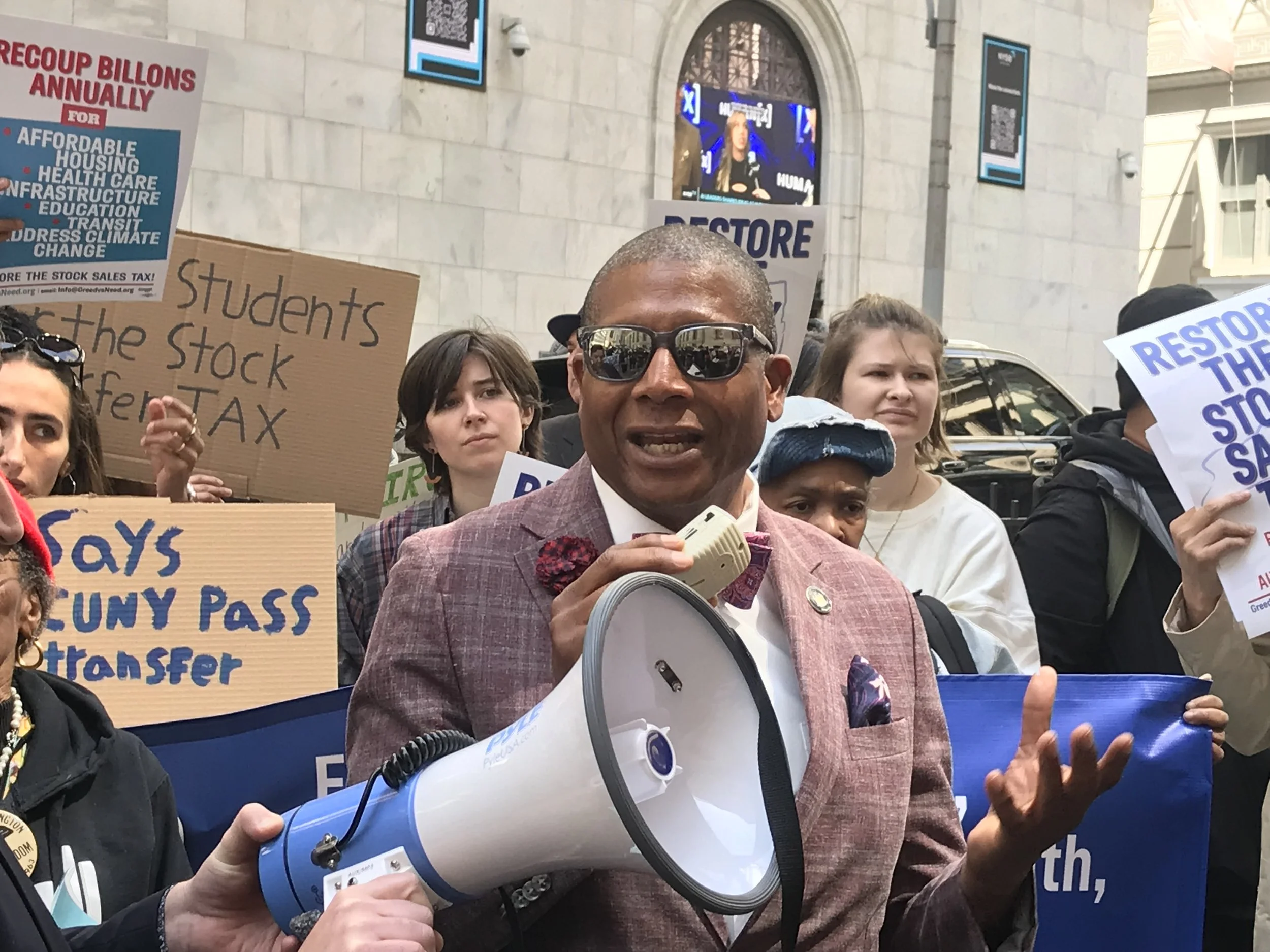

State Senator James Sanders Jr. stands with some of his supporters pushing to finally repeal New York’s stock transfer tax rebate.

The bill would earmark 35% of revenues for transportation, from mass transit to constructing and repairing roads and bridges; 25% for the environment, such as clean-energy projects, sustainable farming, and clean-water infrastructure; and 15% for public education, for primary and secondary schools and the city and state university systems. The rest would go to health care, aid to local governments, and affordable housing—5% to the New York City Housing Authority, and 5% to the state housing agency, for upstate and Long Island.

It has 18 cosponsors in the Senate and 35 in the Assembly, but has been stuck in committee in both chambers without any action since January. Steck told Work-Bites he didn’t expect it to pass this year—"barring a calamitous Trump budget.”

Sanders says he suspects that if the “orange guy” imposes devastating cuts in funding for New York, the number of legislators backing the bill “will triple.”

‘Incredible budget hole’

The tax was enacted in 1905, but in 1977, Gov. Hugh Carey signed a bill to phase it out, so that by 1981, all payments would be rebated. The idea came from then-mayor Abraham Beame, who called the tax “the largest single obstacle to the competitive position of the New York financial community in national securities markets.” In 1981, defending his record during the 1970s fiscal crisis in a letter to the New York Times, Beame cited the stock-tax phaseout, the elimination of 65,000 municipal jobs, and the end of free tuition in the City University system as his achievements.

Ending collection of the tax was “the dumbest thing the state ever did,” says Steck.

Advocates rally in front of the NY Stock Exchange this week urging legislators to stop rebating billions of dollars to Wall Street each year.

The rebates “created an incredible budget hole” for the city while it was in receivership after the fiscal crisis, longtime organizer Judy Jorrisch told the rally. It had to borrow money at the soaring interest rates of the era, which reached 19% in 1981.

The fiscal crisis, she added, was the moment “the city shifted from a citizen-centered government” to one “at the service of Wall Street.”

In 2014, Gov. Andrew Cuomo unsuccessfully tried to include repealing the tax in the state budget.

Would Wall Street move?

The main argument against taxing stock transfers is that as New York would be the only state that does, Wall Street firms would either leave New York or move trading to out-of-state online services.

“Firms might avoid the tax by using new technology or relocating the trading portion of their businesses outside New York,” the Citizens Budget Commission wrote in 2020. Enforcement would be challenging, it said, because there are no clear regulations about “whether a transaction executed on an out-of-state computer server would have a tax liability in New York.”

After Sweden levied a 2% tax on stock transfers in 1984, it added, 30% of trading on the Stockholm exchange moved to London. The United Kingdom, however, has a stock-transfer tax that ranges from 0.1% to 0.5%.

The stock tax is basically a sales tax, Steck responds, and sales taxes only discourage spending if they’re too high. The proposed New York tax is “minimal,” he says, especially for higher-priced stocks. Someone buying 100 shares of Ford for $970 would pay $2.50, while someone buying 100 shares of Apple for $20,000 would pay $5.

“Wall Street would not move,” he told the rally.

New York needs to “rebalance” its economy, Steck told Work-Bites, especially in “areas that have been hollowed out” by the finance-dominated economy of the past 50 years. “One of our biggest resources is finance.”

The money raised by the tax could pay to “build housing that’s affordable based on people’s incomes,” Elizabeth Mackey of VOCAL-NY told the rally. It could also fund the New York Health Act, which would create a state universal health-care system, Dr. Donald Moore of Physicians for a National Health Program told Work-Bites.

The revenue would mean “billions of dollars a year to do social good,” instead of returning it to “hedge-fund people and stock speculators.” says Ray Rogers, head of the End Stock Transfer Tax Rebate Campaign and Corporate Campaign. “It’s long past time.”