NYC Retirees Sue to Cancel New Copays

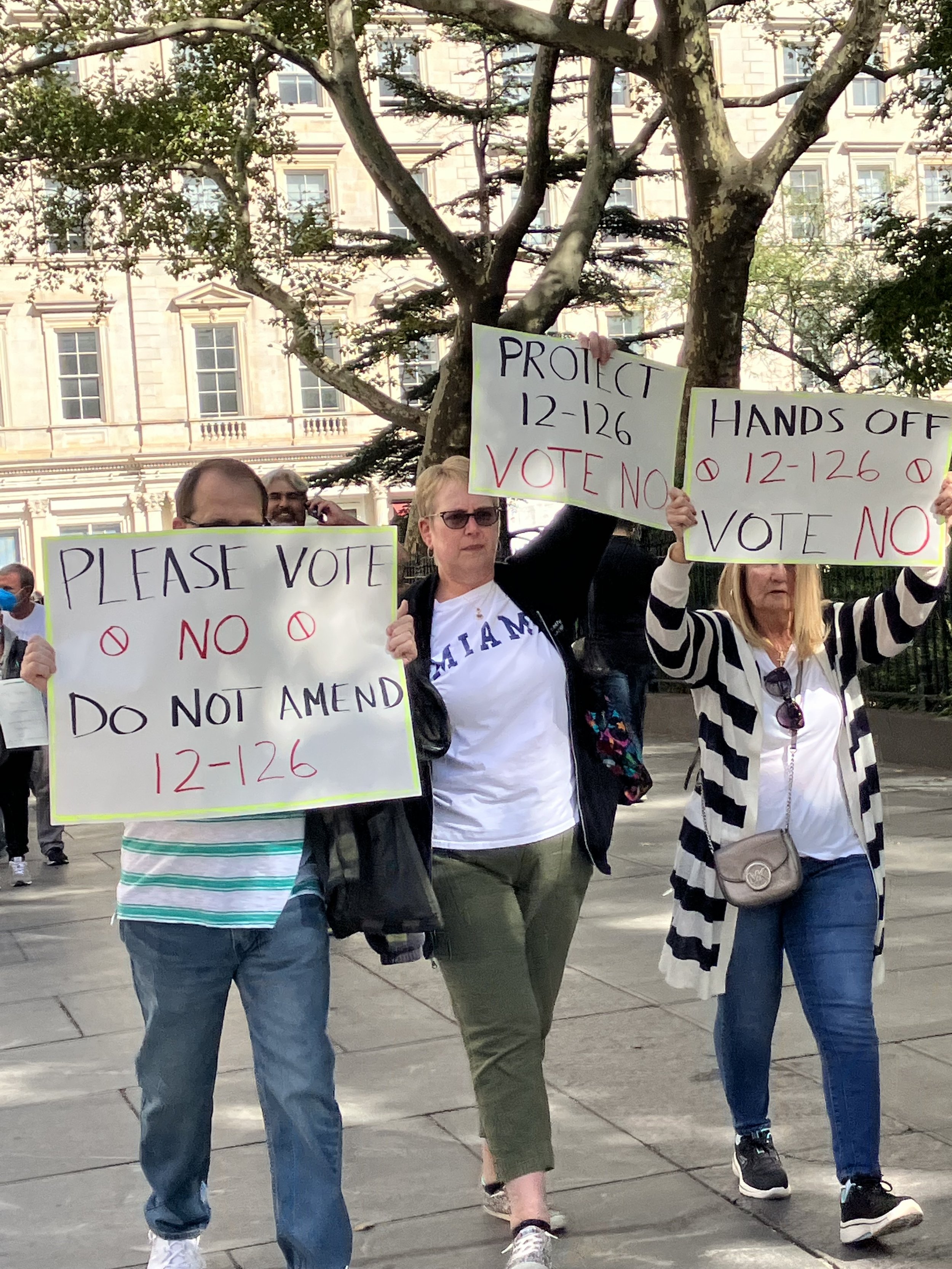

Municipal retirees in New York City have been fighting for more than a year against efforts to push them into an inferior for-profit private health insurance plan. Photo by Joe Maniscalco

By Steve Wishnia

A group of retired city workers is asking state courts to stop the $15 copayment for medical treatment the city and its health-insurance companies began charging in January.

The class-action suit, filed in State Supreme Court in Manhattan Nov. 29 by the New York City Organization of Public Service Retirees against the city government, its Office of Labor Relations, and the EmblemHealth and GHI companies, seeks an injunction to cancel the copayments added for retirees in the SeniorCare health plan for every time they see a doctor or undergo a medical procedure.

It argues that the copays breach the city’s contract with an estimated 183,000 retired workers; violate state Supreme Court Judge Lyle E. Frank’s March ruling that “specifically prohibits the city from passing along any costs of SeniorCare to retirees”; were illegally imposed without the knowledge or consent of retirees who signed up for two years of SeniorCare in October 2020 expecting that they would not have any copayments; and put an excessive burden on people living on fixed incomes.

The $15 may not sound like very much, NYC Organization of Public Service Retirees President Marianne Pizzitola told Work-Bites, but it adds up for people who have to go for chemotherapy twice a week, or for physical therapy three times. The charge is also imposed for procedures such as blood tests, she says, and if a doctor or clinic is affiliated with a hospital, “they’re also hitting us for $15 for a ‘facility fee’” that hospital outpatient departments are allowed to charge.

One couple who are plaintiffs in the suit have already seen doctors 98 times this year, for more than $1,400 in copays, it says. Another plaintiff, a retired teacher, has already paid the $15 for 15 visits, has 21 more scheduled before the end of the year, and also needs surgery.

Many retired city workers get pensions of less than $1,000 a month, says Pizzitola, such as a school crossing guard whose income from her pension and Social Security is less than $2,000, so the cumulative cost of copays cuts into their budget for essentials — or means they can’t afford to buy medicine or hire a home health aide.

“You’re on a fixed income. You can’t pick up an extra shift,” she adds. “Health care isn’t a luxury. It should be a human right.”

The case grows out of retirees’ attempt to stop the attempt by Eric Adams’ and Bill de Blasio’s administrations to switch them from traditional Medicare plus SeniorCare (which covers the 20% of costs that Medicare doesn’t pay) to a private Medicare Advantage plan, with the collusion of several major city union leaders.

“We started getting lots of complaints by June,” says Pizzitola, from people who had used up their deductibles for the year or needed multiple doctor visits to make up for ones they didn’t make during the peak of the COVID epidemic.

The city and the largest unions in the Municipal Labor Committee insist that escalating health costs are forcing it to make changes to avoid having to impose premiums on all workers. They are calling on their members to urge the City Council to amend the city ordinance Judge Frank said the Medicare Advantage plan violated, and launching a campaign to demand that hospitals cut costs.

Medicare Advantage opponents dispute that need. “What the City is really trying to do is to abort its current obligation under law to pay for health insurance coverage for older city retirees and their spouses,” John Murphy, former executive director of the New York City Employees’ Retirement System, said in a November message to Stuart Eber, president of the Council of Municipal Retiree Organizations of New York City, obtained by Work-Bites.

Murphy said that providing GHI supplemental insurance for about 160,000 retirees cost the city $512 million in the 2022 fiscal year, and it could save more than that by reducing administrative expenses and investment fees for its five pension systems.

The lawsuit also argues that in addition to violating city workers’ union contracts, the copayments also violate the longstanding social contract with public-sector workers: Take lower pay than you might get in the private sector, but get a better pension and health care when you retire.

“This was promised to us from the day we were hired, and now they want to take it away,” says Rose Ann Goldberg, 75, a retired school secretary and United Federation of Teachers member. One reason she and her husband, a retired corrections captain, took public-sector jobs, she adds, is because they guaranteed a secure retirement.

“What the active workers don’t understand is that if they touch that amendment, it’s going to affect their benefits,” Goldberg says. “Our unions are not doing their jobs. They’re not protecting us.”