NY Home Health Aides Sue Labor Dept. for Dropping Wage-Theft Probe

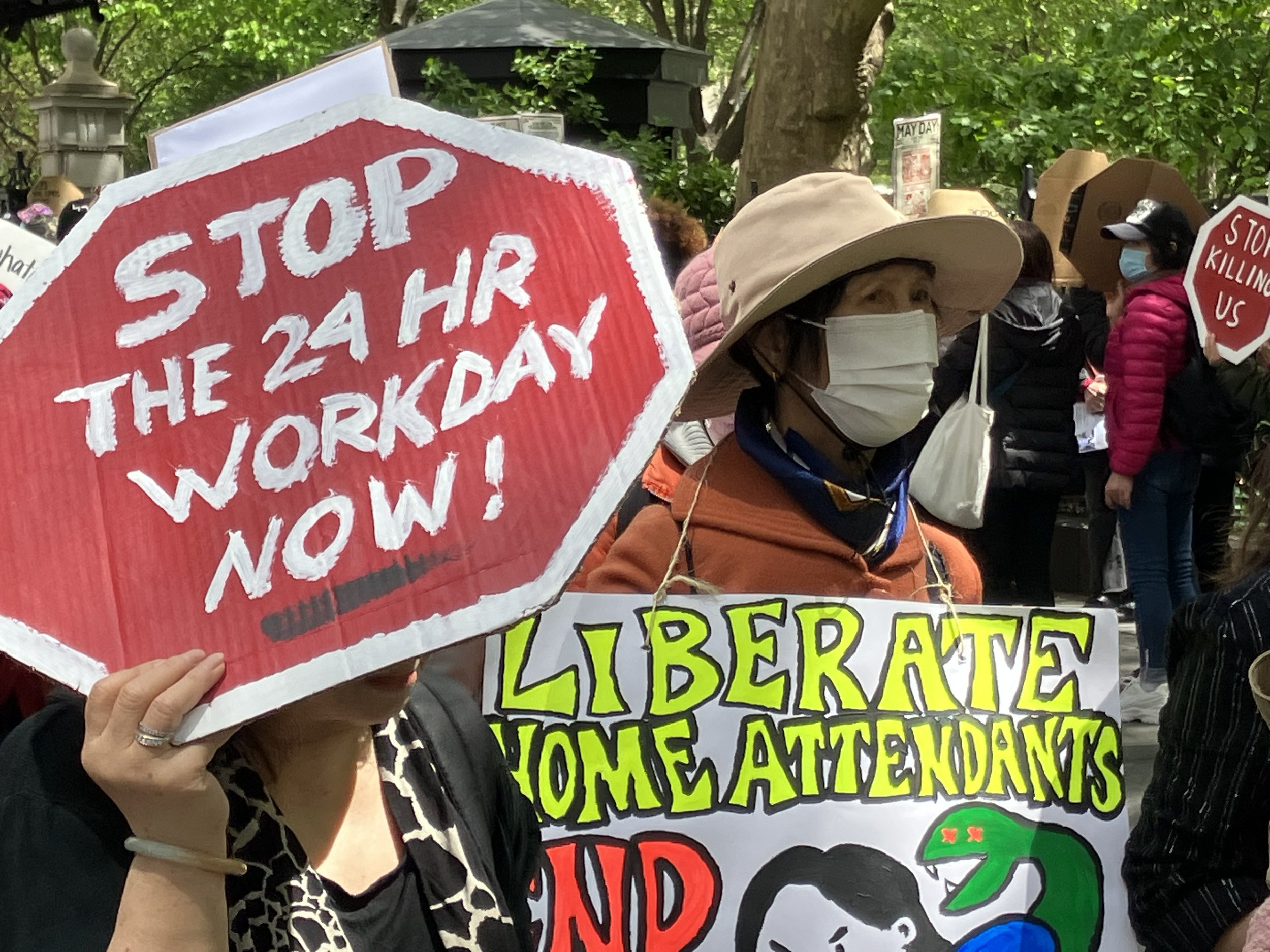

Home health aides rally against round-the-clock shifts at a protest held outside City Hall last May. They continue to fight back in court and on the streets on NYC. Photo by Joe Maniscalco

By Steve Wishnia

Five current or retired home health-care aides are demanding the state Department of Labor reopen its investigation into their wage-theft complaints. In a class-action suit filed in late August, they allege the department’s decision to end its probe after four years was “arbitrary and capricious,” says Carmela Huang of the National Center for Law and Economic Justice, one of the lawyers representing them.

The five women, all in their sixties, allege their employers cheated them out of amounts ranging from $80,000 to $249,000 each for working 24-hour shifts where they did not get the legal minimum of five hours’ sleep. While New York state regulations say employers can pay home-care aides for only 13 hours of a 24-hour shift, the Court of Appeals ruled in March 2019 that workers should get paid for the full 24 hours if they could document that they had not gotten five hours of uninterrupted sleep. The five plaintiffs all filed such forms.

The Labor Department, according to the suit, began its probe in early 2019, and by that December had found “overwhelmingly corroborative” evidence of wage theft. But in April 2023, it began sending letters to about 200 workers who had filed claims telling them the investigation was being closed. The letters were vague, Huang says, but the department’s main rationale was that it could not investigate wage-theft claims filed by workers whose union contracts required disputes to be settled by arbitration.

“It was a political decision,” avers Assemblymember Ron Kim (D-Queens). “We feel strongly that the Department of Labor should enforce the law.” He suspects there was pressure from Gov. Kathy Hochul’s administration to protect the nonprofit agencies that provide home health care, as they would be on the hook for back pay owed.

A Labor Department spokesperson said they “cannot comment on pending litigation.” The department must file a response in State Supreme Court in Albany by Oct. 10.

‘NO RECOURCE’

The case is an “Article 78” lawsuit, a complex form of litigation used to challenge actions by the state government. It argues that the Labor Department’s claim that it can’t interfere if workers have an arbitration agreement is both legally erroneous and did not go through proper rulemaking procedures. Arbitration agreements do not preclude enforcing labor law, it says, noting that the federal Labor Department ignores them while prosecuting violations. The Supreme Court upheld that principle in 2002, Assemblymember Kim and six other legislators wrote in a letter to state Labor Commissioner Roberta Reardon.

Four of the plaintiffs are members of 1199SEIU, which had an arbitration provision in its 2015 contract for the roughly 100,000 home health-care aides it represents. In January 2019, the union filed a complaint alleging that workers were not getting paid for interruptions to sleep and meal breaks during 24-hour shifts. In February 2022, an arbitrator ordered 42 home-care agencies to contribute a total of $30 million to a special fund to reimburse the estimated 5,000 to 8,500 workers who did 24-hour shifts for unpaid wages and overtime.

That settlement, however, yielded far less than what the workers were actually owed. The largest amount paid out has been about $18,000, according to an 1199SEIU online posing cited in the suit. The four plaintiffs who are 1199 members did not submit claims under the arbitration settlement.

The fifth, Chun Feng Zhuang, 69, was listed as a member of the Home Healthcare Workers of America, Local 1770, which also signed a mandatory arbitration agreement. That organization is part of the International Union of Journeymen and Allied Trades, a collection of dubious unions with numerous ties to organized crime, also involved in private garbage collection, fuel-oil delivery, the building trades, and most recently, the cannabis business.

Zhuang said she had no idea she was in a union, according to the suit.

According to the suit, the Labor Department’s letters said the workers had other recourses to seek back pay. However, they couldn’t sue their employers, because of the arbitration agreement, and the September 2022 deadline for signing up for payments under 1199’s settlement had passed. At least 120 workers who did not sign up, it says, had their cases closed.

Without the Labor Department’s intervention, the suit argues, they “have no meaningful recourse for obtaining their unpaid wages and no effective mechanism for ending the egregious wage theft that pervades the home care industry.”

In October 2022, the Chinese Staff and Workers’ Association, National Mobilization Against Sweatshops, and the Flushing Workers’ Center also filed a discrimination complaint with the federal Departments of Health and Human Services, saying that as the majority of home health aides in New York are immigrants and Black, Latino, and Asian women, not paying them for 24-hour shifts violates Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

“If there were different people doing the job, this practice would not be allowed to exist for so long,” says Huang, who is representing the groups filing the complaint.

Vicious circles

Assemblymember Kim says the root of the problem goes back to the 1980s, when New York began outsourcing social services to private nonprofit providers. “New York punted this to third parties, and this is what we’re left with,” he says. In contrast, he continues, California required all counties to create a home-care authority, and that system is very transparent.

The problem is exacerbated in New York City because it has high demand for home care, but the low pay makes it difficult to find workers. “That’s when people start taking shortcuts,” Kim says. Employers recruited workers for 24-hour shifts knowing they couldn’t pay overtime, and many workers “had no idea they were waiving their rights” when they signed arbitration agreements.

The state has been treating home-care employers as if they were government agencies, he adds. “We’re giving them immunity in enforcing a basic wage law.”

If employers are allowed to use arbitration to bypass labor law, that’s a “very dangerous precedent,” and “not democracy,” Kim says. “This lawsuit is critical in determining the future of workers beyond home care.”