‘No Contract, No Coffee!’ - Starbucks Workers Strike on ‘Red Cup Day’

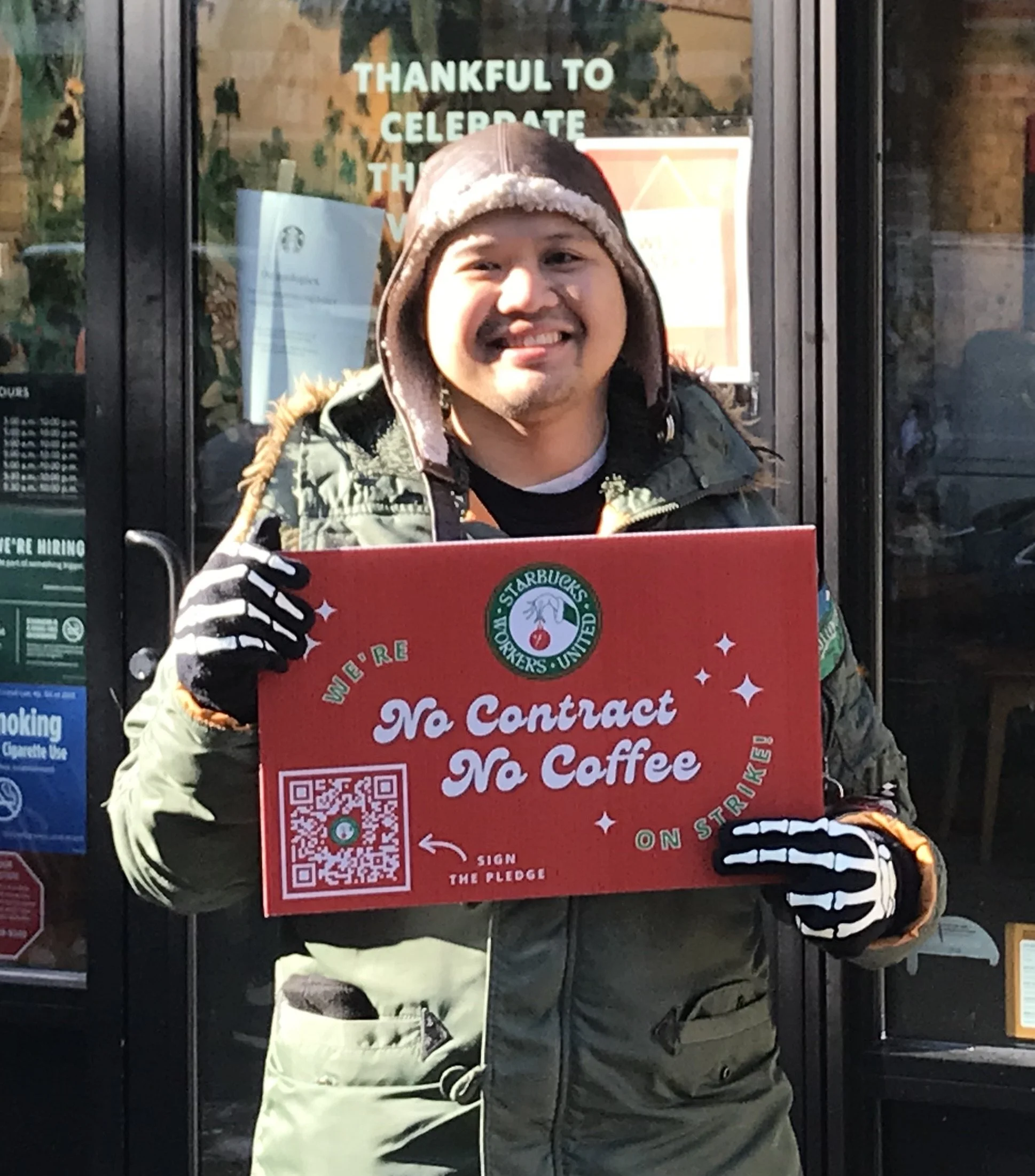

Red Cup Day or not, Starbucks workers in more than 100 stores nationwide walked out on Nov. 17. Photos by Steve Wishnia

By Steve Wishnia

“Are you guys striking?” a young woman in a wool cap and ponytail asks a barista handing out flyers in front of a Starbucks in Queens, November 17.

Yes, says barista Faith Bianchi, giving her a short overview about the workers seeking benefits. “I was going to get some lattes, but I won’t,” the woman answers. A man standing nearby holds a “No Contract, No Coffee” sign, its red and green colors matching the holiday cups Starbucks is giving away.

“Starbucks is refusing to bargain a fair contract,” Bianchi says as she returns to the Starbucks Workers United union’s table on the curb, on 31st Street under the Ditmars Boulevard subway station in Astoria.

The workers at the Ditmars Boulevard Starbucks were part of a one-day strike at more than 100 stores around the country to demand that the company negotiate with their newly organized union. Seven stores in the city, one on Long Island, and two in New Jersey joined the walkout, timed to coincide with the company’s annual “Red Cup Day” promotion. Others included stores in Buffalo, Austin, Chicago, Memphis, Bellingham, Washington; Jacksonville, Florida; and Overland Park, Kansas.

At Ditmars Boulevard, all the workers scheduled for the day stayed out except for one manager and one shift supervisor, so the company had to bring in staff from other stores, says Austin Moran, a union member fired five days after the staff voted to join Starbucks Workers United last summer. “We convinced one to join the picket line,” he adds.

The Astoria Boulevard store a half-mile south, which normally opens at 5 a.m., stayed shut until 9:30, Brandi Alduk said as the seven or eight baristas picketing packed up in the early afternoon. The only workers who went in, she added, were “scabs and management.”

The staff there voted for the union in June, but “we don’t have a bargaining date, and they’ve walked out of bargaining all across the country,” Alduk says. The issues are “the central reasons we started organizing” — understaffing, pay, scheduling, and respect.

Nearly half the 260 unionized Starbucks have not gotten even a bargaining date yet, says Leanne Tory-Murphy of the New York-New Jersey Regional Joint Board of Workers United, the Service Employees International Union [SEIU] affiliate backing Starbucks Workers United.

The union and individual workers have filed more than 250 unfair-labor-practice complaints with the National Labor Relations Board since the organizing campaign began in Buffalo last year. In June, the NLRB’s Buffalo regional office consolidated more than 30 complaints filed by Starbucks workers in Western New York. The charges include refusing to bargain, promising workers better pay and conditions if they didn’t join the union, and threatening or penalizing union supporters.

At Ditmars Boulevard, all the workers scheduled for the day stayed out except for one manager and one shift supervisor, so the company had to bring in staff from other stores.

Federal law requires employers to recognize unions that win an NLRB-supervised election, but it does not set a deadline for a first contract agreement. The Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, passed by the House in 2021, would have required mediation if new unions don’t reach a contract deal within 90 days, with arbitration if mediation doesn’t work. It went nowhere in the Senate when the Republican minority threatened to filibuster it.

Starbucks acknowledged receiving a message from Work-Bites, but did not respond to it.

‘Red Cup Rebellion’

Red Cup Day is a major promotion for Starbucks: Customers who order fall or holiday-themed drinks, such as a caramel brulée latte, get a red plastic cup decorated with a green Starbucks logo and snowflakes. They will spend $8 on drinks to get the cup, says Alduk.

The day, one of the busiest of the year, also highlights understaffing, says Moran: “We get slammed.” Management did not respond to a petition from the Ditmars Boulevard staff asking it to put more than the usual three or four baristas on shifts during the holidays season, he says.

Moran was axed in July for allegedly violating Starbucks’ COVID-safety protocols, and filed complaints charging that his termination was retaliation for his union activity. Both the National Labor Relations Board and the city Department of Consumer and Worker Protection have offered settlements in which Starbucks would rehire him and give him back pay and restitution, he says, but the company refused, so the case will go to trial.

“Starbucks workers are on strike,” picketers standing near the Ditmars Boulevard store call out to potential customers, handing them flyers. Some customers ignore them. Three men decide to walk on after a short conversation. A middle-aged woman takes a flyer and then opens the door with a dismissive scowl.

“Come to Local 79 and make some real money,” a Laborers Union member stopping at the table tells the strikers, then shows them his damaged fingers. “Stay tough,” he urges.

Two women taking a flyer open the door, hesitate, and decide not to go in. A woman pushing a stroller slips in past them.

The substitute shift supervisor comes out and tells the picketers, “You can’t tell people not to come in. I respect you guys, respect me.” They dismiss him. What they’re doing is legal as long as they don’t block the door or harass customers.

“The norm for Starbucks is we’re constantly overworked, underpaid, and understaffed,” says Ditmars Boulevard barista Jules Fuentes. “We want some recognition. We love making coffee. We love our customers.”

Starbucks has long touted its coffeeshops as a “third place,” a place neither work nor home where people can hang out and be part of a community. “We’d love for that to be the case,” Fuentes says. But without enough staffing to give customers individual attention, that’s not going to happen, he adds. “Corporate expects us to churn out drinks like a machine.”