Progressive City? Home Health Aides Demand NYC Abolish ‘Slavery’ of 24-Hour Shifts

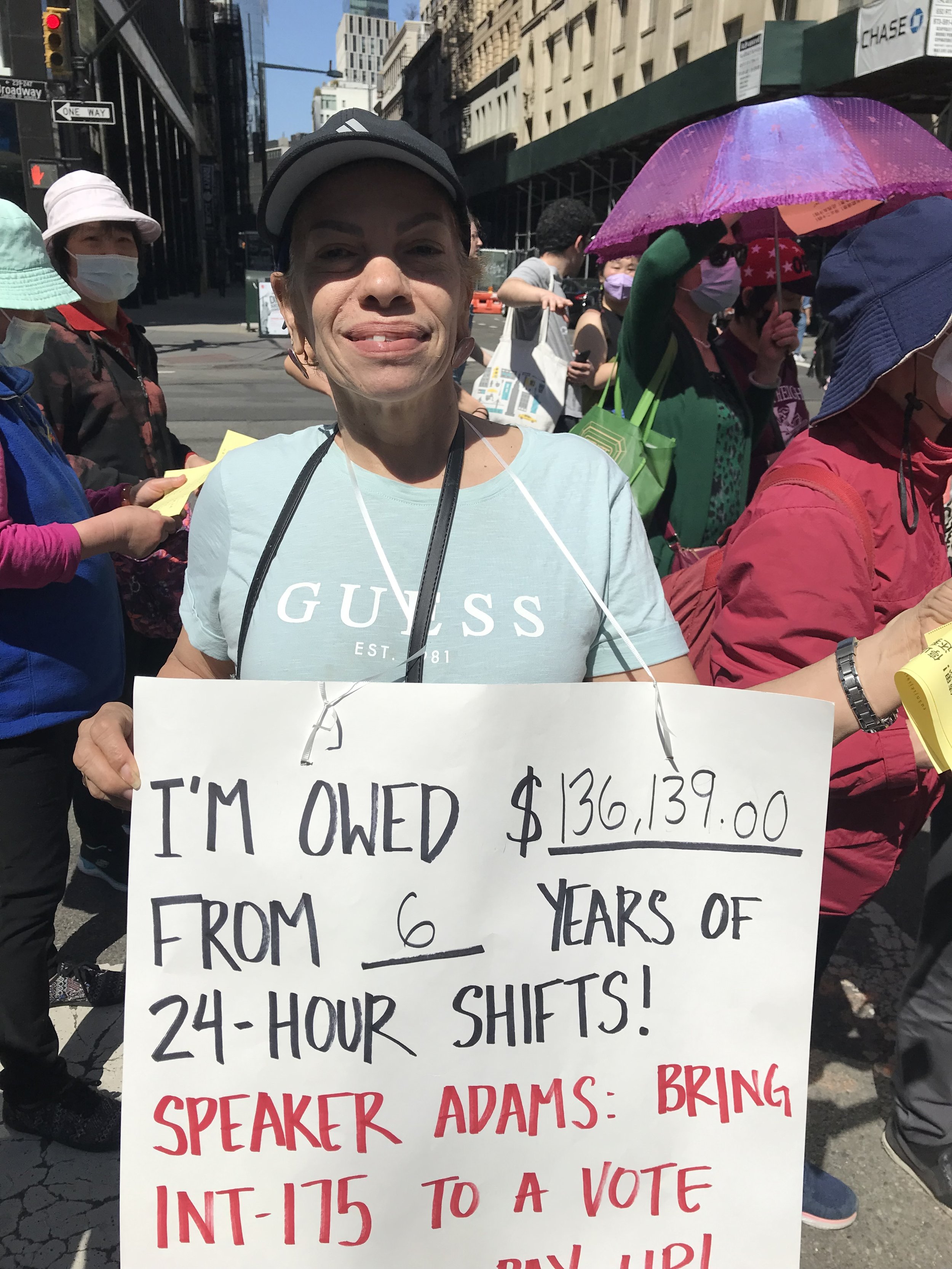

Owed $136,139.00! Home health aides in New York City are calling on City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams to pass the “No More 24 Act”. Photos by Steve Wishnia

By Steve Wishnia

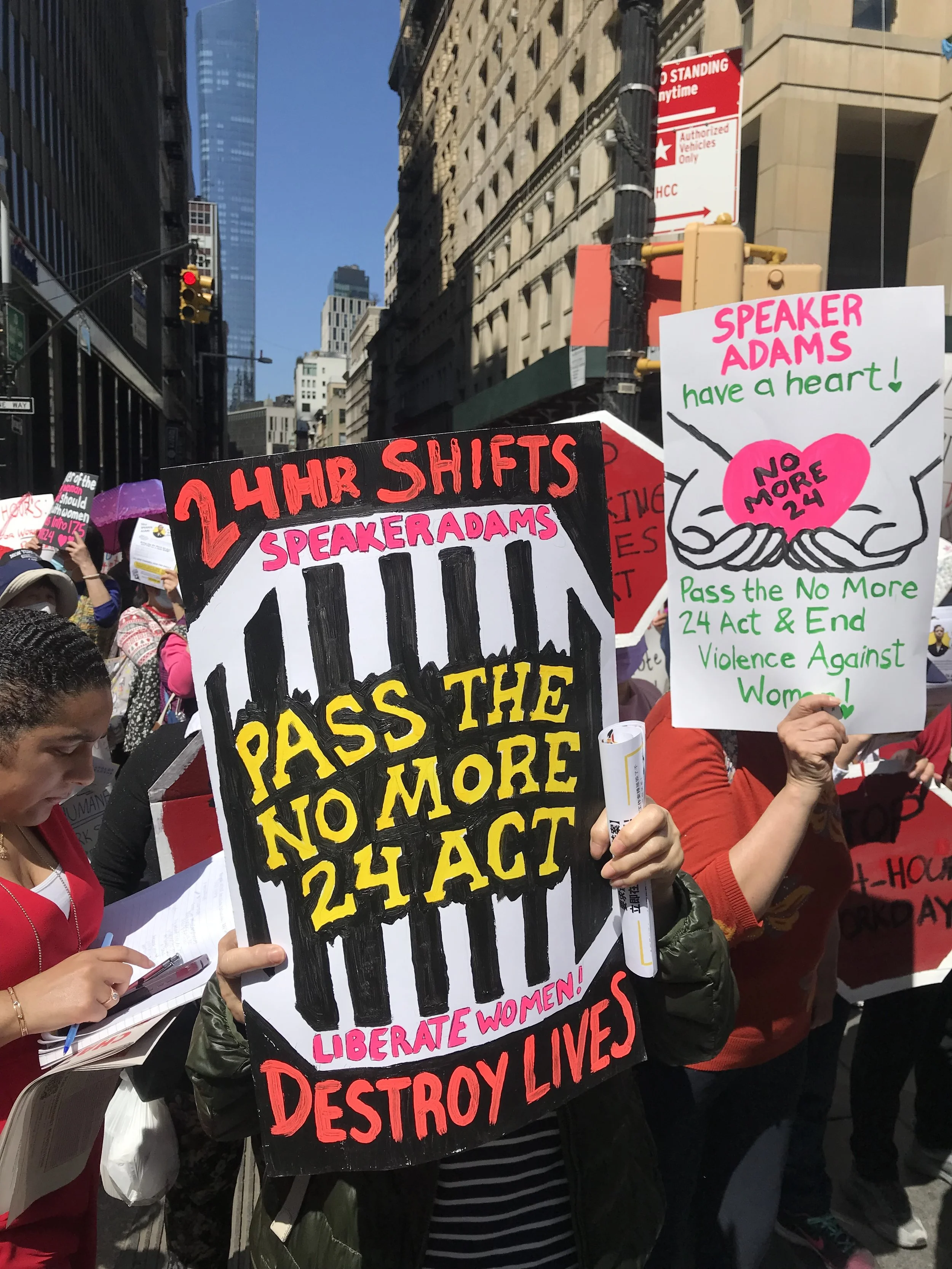

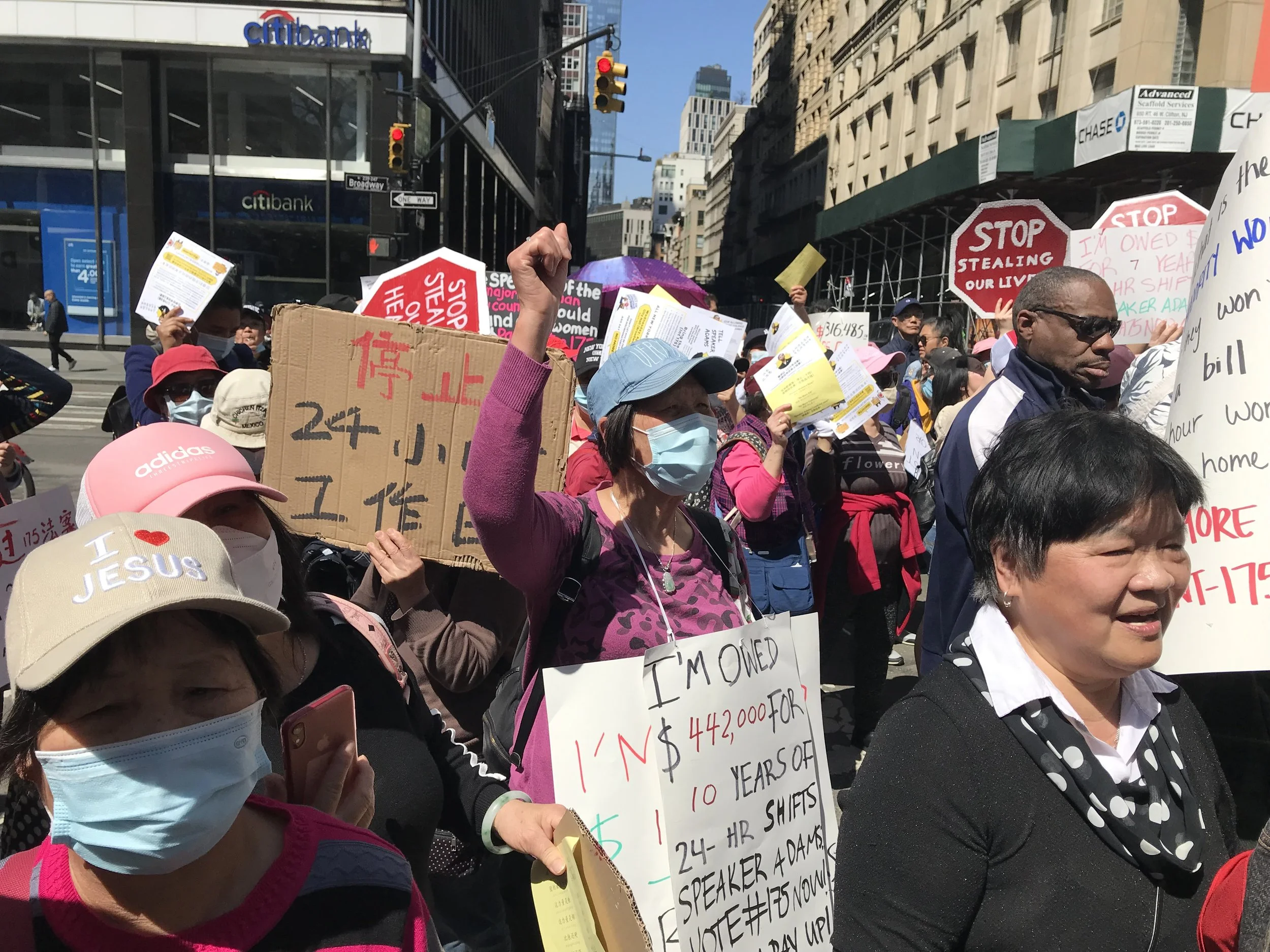

Hundreds of home health-care attendants packed the sidewalk outside City Hall on Apr. 12, demanding that the City Council pass a bill to limit their shifts to 12 hours and end the system of them working 24-hour shifts for 13 hours’ pay.

“I couldn’t sleep for even one hour,” attendant Nu Jun Zhu, speaking in Chinese through a translator, told the crowd. The justification for paying aides for only 13 hours of a shift is that they’re supposed to be resting during the other 11 hours, but, Zhu said, “my patients had to be lifted from a wheelchair to the toilet 20 times a day.”

The state Department of Labor has calculated that she’s owed at least $235,000 in back pay and damages for the nights she had to work. Meanwhile, she said, she can no longer write, because of arm and finger injuries sustained during her eight years of working more than 70 hours a week.

The protesters accused Council Speaker Adrienne Adams of refusing to schedule a vote on the bill, Intro 175-A. Her “indifference allows racism and slavery to continue,” attendant Marcola Guzman told the crowd.

“Intro 175-A had a hearing and continues to go through the Council's legislative process,” a spokesperson for the Speaker told Work-Bites earlier this week.

Eight of the bill’s cosponsors have withdrawn in the past week. Councilmember Christopher Marte (D-Manhattan), its lead sponsor, told the rally that other members have been asking him if he fears he’s risking his political future by continuing to push the legislation. He said he was inspired to keep going by the courage of the women whose employers had threatened them with being fired, sued, arrested, or blacklisted if they continued to speak out.

Marte told Work-Bites he was frustrated that supporters of the bill had worked with disability-rights groups and the unions representing attendants to amend it, but “still, we haven’t gotten anywhere.” He declined to say where the political pressure on its supporters was coming from.

“I don’t think it’s a budgetary issue,” he continued; the budget is being used as “an excuse to not do anything.” Some of the agencies that arrange care and hire attendants have ended 24-hour shifts without getting additional Medicaid funding, he said.

The amendments added since a hearing on the bill last September include delaying its effective date until Oct. 1, to give the state, the city, and home-care agencies time to prepare for the end of 24-hour shifts.

Meanwhile, the state Labor Department has found that more than 550 attendants are owed back pay and damages for having to work during times when they were supposed to be getting rest.

It will be a while before any of them collect any of that, though. Mei Xian Li, 76, who retired last year, received letters from the department last October, stating that she’s owed a total of $463,000 in back pay and damages from two agencies. The letters offered to schedule mediation sessions with her former employers. So far, nothing has happened, she told Work-Bites.

Workers might end up having to sue their employers for the back pay, Marte told Work-Bites.

Li did 24-hour shifts four or five days a week for eight years — “lack of sleep, lifting patients, turning them, lifting them to go to the bathroom or change them.”

“Everywhere on my body hurts,” she says, speaking in Chinese through a translator. “We must abolish the 24-hour workday.”

The Intro 175-A bill is “preventative,” JoAnn Lum of the National Mobilization Against Sweatshops, one of the groups in the Ain’t I A Woman campaign, told Work-Bites as the noontime rally ended, as it will stop wage theft by ending the ‘24 hours work for 13 hours pay’ system. The more Speaker Adams does not allow it to go forward, she added, “the more wage theft there will be.”

Home health aides rally outside City Hall this week demanding action on Intro. 175-A.

“It’s like we work the night as a gift to them,” says attendant Trinidad Castro, a 47-year-old mother of six children, speaking in Spanish through a translator.

She just came off a 24-hour shift, caring for an 85-year-old woman. “I have to turn her, change diapers, calm her down so she can sleep,” she says. Her wrists and back hurt, she adds. Ain’t I A Woman estimates she’s owed more than $100,000 for 24-hour shifts in the past six years.

Valeria Guerrero, a home-care attendant since 2000, had to retire last December after she tripped and fell while bringing her patient’s dinner plate to the kitchen. She shows the back brace she’s wearing under her pink T-shirt.

“You can’t sleep. You get high blood pressure. You’re nervous. It’s an abuse,” she said, also in Spanish. Sometimes she had to stay on the job for seven days straight or longer, she adds, and the agency would split her paycheck into two parts to avoid having to pay her overtime. Other times, after she’d worked three days, she’d have to stay for a fourth if her replacement was late — and her agency wouldn’t pay her for the extra time.

She believes the best system would be to have four people split the workweek, each doing 12-hour shifts.

Ain’t I A Woman estimates she’s owed more than $350,000.

“A century and a half ago, we were in the streets fighting for an eight-hour day— ‘eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours to do what we want,’” Lum said. “Now, we’re fighting to end 24-hour shifts. And this is supposed to be a progressive city.”