Phil Cohen War Stories: The Textile Cowboys

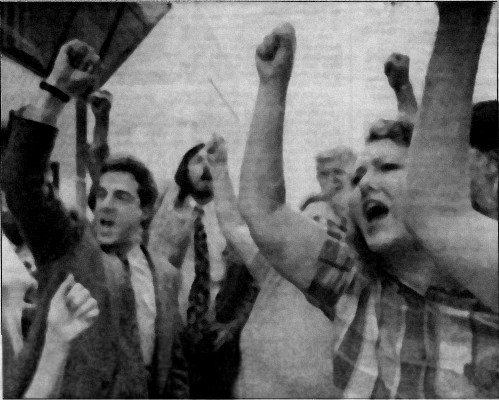

Vintage shot of the Greif plant protest. Photo/Harry Fisher/The Morning Call

WAR STORIES By Phil Cohen

In 1976, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America and the Textile Workers Union of America merged to form the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union. It was a marriage of convenience, rooted in necessity, between very disparate cultures. The Textile Workers were renowned for organizing muscle but on the verge of bankruptcy. The Clothing Workers were complacent in the field but had amassed an enormous treasury.

Fifteen years later, two very antagonistic leadership groups governed the union. Regions consisting primarily of cotton mills were run by the old Textile Union vanguard that aggressively invested resources in organizing campaigns. Clothing dominated regions continued to hoard assets in favor of proactive field work.

The president, secretary treasurer, and executive vice president of ACTWU were all members of the Clothing faction, but the largest and most powerful affiliate of the merged organization was the Southern Regional Joint Board—in the heart of textile country. It was directed by a cunning and ruthless international vice president named Bruce Raynor. His vision for the union was “growth at any cost.” His vision for himself was becoming national president. He assembled a formidable organizing department that became the envy of union leaders throughout the country, run with an iron fist and zero tolerance for failure. I had been hired as a lead organizer in 1988.

Within the southern staff, an elite cadre emerged to spearhead campaigns against hostile employers and rebuild dysfunctional locals. This small group was directed by Ernest Bennett, who considered me his top field agent. After two years of roaming the South, I convinced Ernest to keep me assigned in North Carolina, so I could remain a father to my young daughter.

In 1993, Bruce Raynor became ACTWU’s executive vice president, expanding his reach and philosophy to a national level. He also remained southern director, using control of the powerful region to bolster the clout of his new position. He did little to hide his contempt for Secretary Treasurer Arthur Loevy, standard bearer for the conservative Clothing clique that prioritized balance sheets over organizing. The rift between the two factions came to a head.

Loevy and his followers despised militant Southern organizing tactics and the expenses incurred. They sarcastically referred to my trouble-shooting unit as The Textile Cowboys. Rather than feel insulted, we adopted the name and wore it as a badge of honor.

The Battle Horn Sounds

ACTWU represented 20,000 workers in the men’s garment industry through a master contract negotiated with the Clothing Manufacturer’s Association. This arrangement was seen as beneficial by both sides of the union’s bureaucracy. It allowed us to maintain control of the industry and was far less expensive than negotiating dozens of small agreements across the country. The contract was scheduled to expire at midnight on September 30.

One of our major clothing employers was Greif, a suit manufacturer with 1,400 hourly workers in three Pennsylvania plants. Several months after Bruce was anointed to national office, Greif was purchased by Genesco, a Tennessee shoe manufacturer.

On Friday, August 13, 1993, I was summoned to a meeting with the North Carolina director. He explained that Genesco had withdrawn from the Clothing Manufacturer’s Association and planned to negotiate a separate contract involving major concessions. Bruce realized that if allowed to succeed other employers would follow suit to the detriment of the union and its members.

The new executive vice president considered the Pennsylvania Joint Board utterly ill-equipped to respond. He’d assigned Ernest Bennett to mount a campaign, who in turn, wanted me to start a revolution in the large Allentown plant. I didn’t relish the prospect of another “away mission,” but this was my kind of action and the stakes couldn’t have been higher.

On Monday, I was headed north on the long, tedious drive to Philadelphia for meetings with Ernest, and then the Joint Board leadership. My staff car at the time was a dark blue Thunderbird. This was the dawn of the digital age and I was one of the first ACTWU field staff to get a car phone. It was very cool on first dates. An attractive young lady, already impressed by the vehicle, would take her front passenger seat, turn to face me, see the phone and ask, “Just who the hell are you, James Bond?”

I checked into a luxury hotel room in downtown Philadelphia that had been reserved for me, unpacked and knocked on Ernest’s door. He was a short, stocky man about my age, prematurely bald and overflowing with manic energy. Like me, he’d left home at sixteen and was self-educated. However, he was from an affluent family and didn’t share my working class background. “How was your trip?” he asked, shaking my hand.

“About as delightful as the last time I spent twelve hours on the interstate.”

“Okay look, let’s get down to it,” he said. I grabbed a chair as Ernest paced around the room. “I need to tell you who you’re gonna to be dealing with. This is a very rich joint board, but the staff is lazy and doesn’t know shit about running a campaign. The director is an international vice president named John Fox. He’s part of Arthur Loevy’s inner circle and hates everything we stand for in the South. Bruce pulled rank and basically shoved you and me down his throat. He resents us being given authority to solve his problems. But still, you’re gonna have to find a way to build a relationship with him so he trusts you enough to stay out of your way.”

Ernest paused a minute as he took a full lap around the room, doing whatever strange inner process he used to recharge his batteries during a twenty-hour day. “There’s a few things you need to understand about John Fox,” he continued. “He’s Jewish, grew up in Eastern Europe during the holocaust and spent his adolescence in a concentration camp, surviving by harvesting corpses and bringing them to the ovens. When the war was over he immigrated to New York, found work as a tailor and became active in the Clothing Workers Union. One thing led to another and he’s been running the Pennsylvania Joint Board for years.”

“That’s a pretty impressive background,” I interjected.

“Yeah, except he’s very temperamental and thinks this city and surrounding counties are his private domain. Look, there are two schools of servicing locals; the business model and the organizing model we use. John prefers the business model. It’s top-heavy and doesn’t involve the people. Negotiations and issues are resolved behind closed doors and all folks get to do is vote. You’re gonna have to pull six hundred workers together and teach them to fight for the first time. The contract expires in six weeks on September 30.

“All I know is the new owners want concessions. What are they?”

“Genesco is proposing a three year wage freeze, $700 health insurance premiums, a cut in vacation, the right to assign jobs without bidding, and subcontracting work at their discretion.

In sum total, it would represent a twenty percent economic reduction from what we expect to get for the other clothing workers. And the point is, Genesco is highly profitable. Think about it. They had the damn money to buy Greif. It’s not like they’re coming to us hat-in-hand. The people are in an uproar but don’t know what the hell to do about it. That’s where you come in.

“The Allentown plant is the heart of Greif’s operation. If we can cripple them there, Genesco will cave in. A new business agent at the joint board named Tony Galfano has been assigned to assist. He’s smart but never been in a campaign. Tony reports to you, not John until this is over. Use him as you see fit.”

Ernest had placed a young organizer, who he would supervise more closely, in the two smaller plants.

The next day, we drove to the Philadelphia Joint Board office. It was like nothing I’d ever seen in the South. John Fox’s organization owned an office building complete with a parking garage and an entire floor dedicated to their private insurance company for union members. Ernest and I had an amicable but strategically unproductive meeting with John. That evening I addressed several dozen Greif workers and the Pennsylvania staff in the building’s large meeting hall.

“I’m here for one reason,” I told them, “and that’s to fight. You don’t know me and therefore wonder if you can trust me. Trust usually grows with time but time is one thing we don’t have. So hear my words, feel my vibes and trust your gut. This is going to be like nothing you’ve ever done before. It will be like riding a roller coaster…perhaps starting slow as it climbs the first hill but suddenly travelling a hundred miles an hour as it heads downhill and around the bends. You’ll have to hold on tight and keep your wits about you. Always expect the unexpected because it will come out of nowhere and hit us in the face.”

This was what the workers had dreamed of ever since joining the union and they stood up, applauding wildly.

Allentown: You Have No Idea What’s Coming!

On August 17, Ernest and I departed on the ninety-minute drive to Allentown. After choosing a motel, we headed to the plant for some preliminary introductions before the one-shift operation exited at 3 pm. The Joint Board had already faxed a document to management informing them I would be servicing the local, assisted by Tony Galfano. We were greeted at the entrance to the production floor by plant manager Tommy Lacocca, to whom I presented myself as an easy going, just-doing-my-job type of business agent. I always offered management that first impression, so their guard would be down when it came time to let things rip.

Ernest left on Wednesday morning and Tony drove in from Philadelphia to accompany me on my first plant tour. The master clothing contract contained unrestricted visitation rights for union reps. I was neatly attired in a grey sports jacket and tie, befitting the culture of northern apparel plants. I’d already met mill chair Clara Moser, president John Nush, and other union committee members during the meeting in Philly, and they’d prepared the membership for my arrival.

Apparel factories are referred to as cut and sew operations in the rag trade. At one end of the building, cutters prepare clothing components from large rolls of cloth. The work involves skill and precision. A sleeve that is 1/16 of an inch too long is absolutely worthless. The workers are the highest paid and primarily male.

The majority of the workforce is women sitting in rows behind sewing machines, divided into departments responsible for attaching one specific item to garments in progress: buttons, zippers, sleeves, jacket collars, trouser cuffs, etc. The work is tedious, stupefying and results in frequent repetitive motion injuries. But the one thing that makes the day pass for sewers is beating the piece rate. Jobs have an hourly rate for achieving 100 percent production as defined by industrial engineers (company and union). Every percent over that number of units increases pay proportionately. An experienced worker who knows the shortcuts can operate at over 130 percent and take home a much larger check. It becomes an almost addictive game.

Tony followed me as we began making our rounds. I stopped at each work station to shake hands and introduce myself saying, “Hi, I’m Phil and I’m here to fight,” speaking loudly enough to overcome the incessant drone produced by hundreds of sewing machines. I’d briefly discuss negotiations and move on. I discovered a quarter of the workers were from Lebanon. They were friendly and understood union but otherwise spoke little English.

I visited the cutting room and met shop steward Tony Barbone, a likeable, down-to-earth guy. It surprised me to find he was steward for the entire local. In the South, each department on every shift had its own steward. He not only didn’t have a copy of the contract but had never seen it. “Only the president and mill chair get to have one,” he told me. This was my first taste of the business model of servicing.

Whatever illusions the plant manager may have had about my presence being symbolic were about to be shattered by the leaflet I wrote that evening. It itemized and denounced Genesco’s proposal and scheduled a union meeting for the following week. In those days, one had to take typed or handwritten copy to a printer with detailed instructions for typesetting, expecting it to get screwed up on the first try. But Tony Galfano was years ahead of me when it came to computer literacy. His first assignment was to prepare the leaflet and run copies.

We returned to the plant the next day, distributing leaflets and letting folks know the cavalry had arrived. As we exited down a long corridor between the production area and front door I spotted a large hole near the bottom of the wall to my right. I pointed to it with my shoe, remarking, “You’d think they’d bother to fix this.”

Phil Cohen spent 30 years in the field as Special Projects Coordinator for Workers United/SEIU, and specialized in defeating professional union busters. He’s the author of Fighting Union Busters in a Carolina Carpet Mill and The Jackson Project: War in the American Workplace.