WGA Strikers Took on the ‘Hollywood Beast’ and Put a ‘Leash on the Robots’

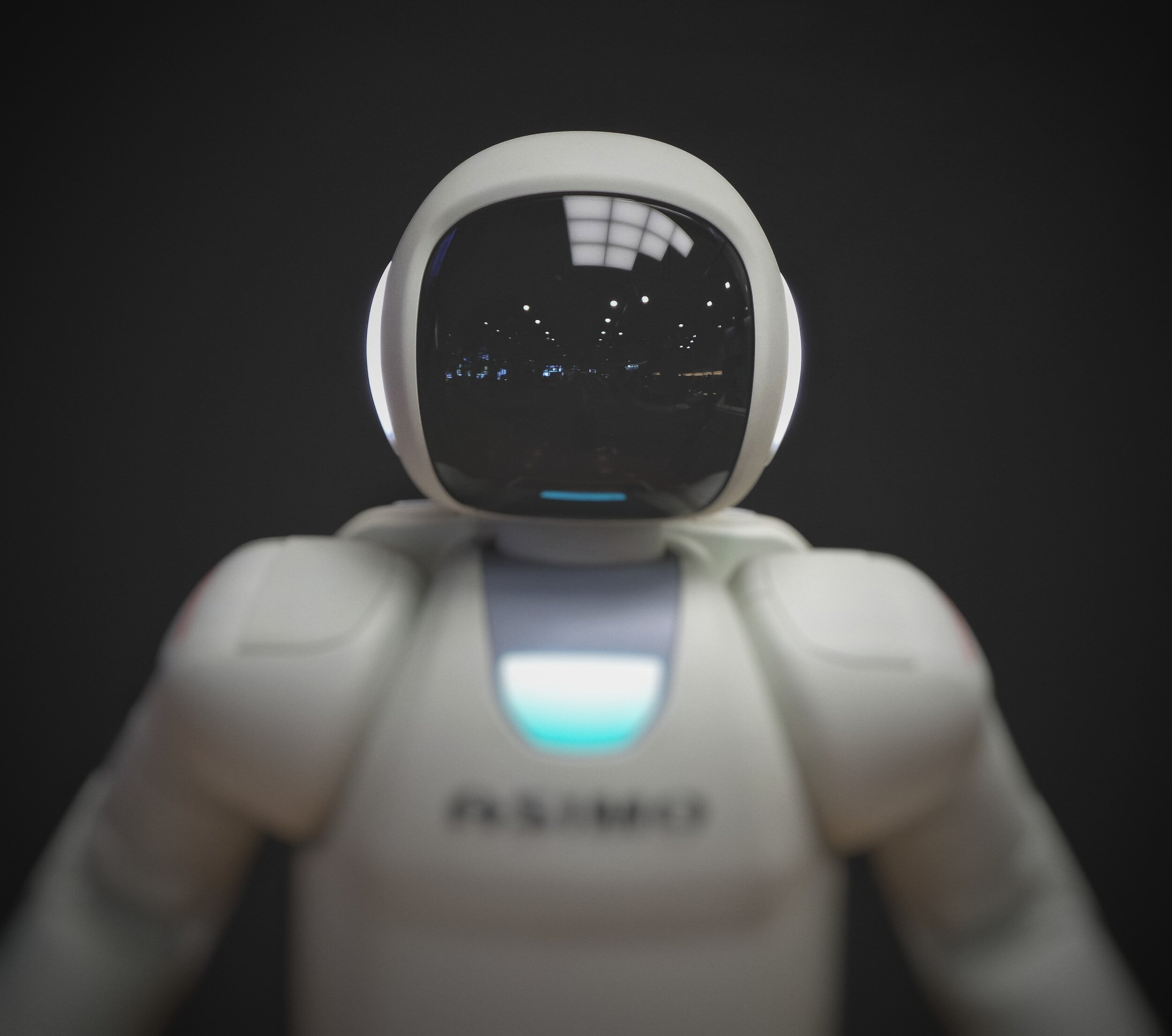

Only the struggle to democratize our work will leash the robots.

By Robert Ovetz

Courtesy of the author

The recently ended 148-day-long Writers Guild of America (WGA) strike by 11,500 Hollywood screenwriters is one of the most important strikes in decades because it tamed the Hollywood corporate beast.

Not only did the writers extract three times the value in concessions originally offered by the companies, but it also provides a number of important wins that address the threat of AI and low-paid precarious work that screenwriters, like so many of us, face.

Their success on both issues, especially automation, will have an impact on the entire working class. It lays an important foundation for the struggles against AI not only for the SAG-AFTRA actors, who were on strike with them since July, but all of us.

As I wrote about in June, AI’s threat to make us all obsolete will not be defeated with news laws or regulations, lobbying or voting. Instead, only the struggle to democratize our work will leash the robots.

That’s what the screenwriters succeeded in doing. Their first victory is not the final word on the issue but it has much to teach us.

Their contract now covers how AI is used in writing scripts and empowers screenwriters to refuse to use any materials produced by AI. The companies must disclose any materials produced by AI and cannot force a screenwriter to use any material produced by AI. While the contract does not prohibit writers’ materials to be used to “train” AI, the WGA has the right to challenge it as a contractual violation.

The screenwriters didn’t fight AI as an issue of privacy, safety, accountability, equity, inclusion and transparency as some nonprofits are doing. Rather, they fought AI as a dangerous weapon used by the boss against workers. AI is first a threat against workers power before it is a threat to individual rights.

The screenwriters’ new control of AI, a first of its kind, is exactly the kind of workers’ control that I often write about on these pages. Rather than serve the robots, the screenwriters can decide whether or not the robots serve them.

AI is expected to do many kinds of work such as writing, administrative support, translation, communications, medicine, law and art and graphic design. The AI industry expects the impact to grow rapidly around the world to make hundreds of millions of workers obsolete in the next couple of years. While these companies like to blow their own horn to sell more contracts and shares, the threat is real.

AI won’t immediately wipe out a large number of jobs. Rather it is being used to break up many types of jobs into their component tasks. Some tasks will be done by AI and others by newly de-skilled gig workers paid far less.

AI is being used as part of the latest effort to break up, automate and de-skill us to get us to work harder for less pay since industrial engineer Frederick Taylor first began his first time and motion studies more than a century ago. His ideas were used to invent the assembly line and continue to be widespread.

Like the assembly line and the computer, the bosses want to use AI to reduce their need for workers while making those they still employ produce more with less pay. As AI is introduced into the workplace, it reduces the number of human laborers and human work hours, while increasing productivity for those workers who remain.

The screenwriters and the actors, who were both on strike together for the first time in 1960, saw the threat and took on the fight. AI was a threat not only to their livelihoods but even to control over their ideas and likeness.

The power to refuse to use AI not only empowers the screenwriters to decide what kind of tools, such as AI, they can use. It also allows them to maintain full control over the creative process and output of their work.

The WGA’s power to control AI is an earth-shattering shift in strategy the workers movement has not seen since the introduction of industrial unions or what we today call “wall to wall” unions. Eugene Debs led the short-lived American Railway Union which organized every type of railroad worker during the weeklong 1894 strike in solidarity with the Pullman strike that shut down the country.

Halting the advance of AI is inseparable from reversing the spread of precarious gig work. The screenwriters were also on strike against the companies turning them into low-paid gig workers. The new CBA establishes minimum staff levels for the “writers’ room” and a guaranteed minimum period of work on TV and streaming productions. Streaming itself is a new technology that has been used to extract more creative work from writers and actors for less pay. The new contract also includes better “residual” pay for their creations reused on the streaming platforms.

The WGA strike put a leash on both AI and precarious work, which are also at the center of the now the three-month-long SAG-AFTRA strike. The actors want to prevent AI from being used to replicate their likeness to produce AI-generated crowds or even series without paying the actors.

The film “The Congress,” starring Robin Wright as herself who sells her own likeness to the studios, was a stark warning to Hollywood workers a decade ago. Today those workers are still on strike to defeat it.

The struggle against AI is a monumental victory we should study closely and expand into our own struggles.

Robert Ovetz is editor ofWorkers' Inquiry and Global Class Struggle, and the author of When Workers Shot Back, and mostly recentlyWe the Elites: Why the US Constitution Serves the Few. Follow him at @OvetzRobert